Presentación

Crisopeya

Revista de Arte y Literatura

(Fernando González en tres idiomas)

—7 de julio de 2022—

* * *

Ver grabación del evento:

YouTube.com/CasaMuseoOtraparte

* * *

«Crisopeya – Revista de Arte y Literatura» es una publicación mensual de circulación digital identificada con ISSN: 2711-4147. En junio de 2022 cerró su segundo año editorial con la publicación total de 24 números. Por sus páginas han pasado diferentes artistas y escritores locales, nacionales e internacionales. A partir de creaciones visuales y textuales multiformes ha presentado diferentes concepciones estéticas, artísticas y literarias. Este año, en alianza con la Corporación Otraparte, ha publicado versiones bilingües en inglés y francés de textos originales de Fernando González Ochoa y de escritos acerca de su obra. El objetivo es dar a conocer a este filósofo y escritor en diferentes círculos literarios y culturales, especialmente entre el público no hispanoparlante de la revista.

Presentación a cargo del

equipo de traducción Crisopeya.

* * *

* * *

Conozcamos a

Fernando González Ochoa

~ Comité Editorial Crisopeya ~

Uno de los objetivos de Crisopeya como revista de Arte y Literatura es la difusión de letras colombianas en diferentes espacios. La traducción a otras lenguas es una forma de alcanzar esa meta y de iniciar múltiples y diversos diálogos alrededor de las obras traducidas. Es una forma hermosa de interactuar con el mundo y de descubrir nuevos sentidos.

Queremos iniciar compartiendo las letras del más original de los filósofos colombianos: Fernando González Ochoa (1895-1964). Por ello, en alianza con la Corporación Fernando González – Otraparte —encargada de difundir y preservar el legado del escritor—, en el marco de su Vigésimo Aniversario, estamos felices y orgullosos de anunciarles un nuevo proyecto en conjunto. En los próximos números de la revista Crisopeya, dentro de esta misma sección, comenzaremos a conocer a este asombroso escritor. Les traeremos los textos originales en español acompañados de su traducción a otras lenguas, algunas notas e imágenes.

¡Acompáñennos en esta nueva etapa!

*

Let’s meet

Fernando González Ochoa

~ Crisopeya Editorial Committee ~

One of the principal objectives of Crisopeya as an Art and Literature magazine is the diffusion of Colombian literature in different spaces. Translating to other languages is a way of achieving this goal and starting multiple and diverse dialogues around the translated works. It’s a beautiful way of interacting with the world and finding new meanings.

We want to start out by sharing the works of the most original of Colombian philosophers: Fernando González Ochoa (1895- 1964). That’s why, in alliance with the Corporación Fernando González – Otraparte —in charge of spreading and preserving the legacy of the writer—, in the framework of its Twentieth Anniversary, we are happy and proud of announcing a new joint project. In the next issues of Crisopeya, in this same section, we will start to know this amazing writer. We will bring you the original texts in Spanish accompanied with their translation to other languages, some notes and images.

Join us in this new stage!

*

Rencontrons

Fernando González Ochoa

~ Comité Éditorial Crisopeya ~

L’un des objectifs de Crisopeya en tant que magazine d’Art et de littérature est la diffusion des lettres colombiennes dans différents espaces. La traduction vers d’autres langues est un moyen d’atteindre cet objectif et d’initier des dialogues multiples et divers autour des œuvres traduites. C’est une belle façon d’interagir avec le monde et de découvrir de nouveaux sens.

Nous souhaitons commencer par partager les paroles du plus original des philosophes colombiens : Fernando González Ochoa (1895-1964). C’est pourquoi, en alliance avec la Corporación Fernando González – Otraparte —chargée de diffuser et de préserver l’héritage de l’écrivain—, dans le cadre de son Vingtième Anniversaire, nous sommes heureux et fiers d’annoncer un nouveau projet commun. Dans les prochains numéros du magazine Crisopeya, dans cette même section, nous commencerons à connaître cet écrivain étonnant. Nous vous apporterons les textes originaux en espagnol accompagnés de leur traduction dans d’autres langues, quelques notes et images.

Rejoignez-nous pour cette nouvelle étape !

*

Lass uns Fernando

González Ochoa treffen

~ Redaktionskomitee Crisopeya ~

Eines der Ziele von Crisopeya als Kunst- und Literaturzeitschrift ist die Verbreitung kolumbianischer Literatur an verschiedenen Orten. Die Übersetzung in andere Sprachen ist eine Möglichkeit, dieses Ziel zu erreichen und vielfältige und vielfältige Dialoge über die übersetzten Werke in Gang zu setzen. Es ist eine wunderbare Art, mit der Welt zu interagieren und neue Sinne zu entdecken.

Wir möchten damit beginnen, die Texte des originellsten kolumbianischen Philosophen zu teilen: Fernando González Ochoa (1895-1964). Deshalb in Zusammenarbeit mit der Corporación Fernando González – Otraparte —die mit der Verbreitung und Bewahrung des Vermächtnisses des Schriftstellers beauftragt ist— freuen wir uns und sind stolz, Ihnen im Rahmen des 20. Jubiläums ein neues gemeinsames Projekt anzukündigen. In den nächsten Ausgaben der Zeitschrift Crisopeya, in dieser Sitzung, werden wir beginnen, diesen erstaunlichen Schriftsteller kennenzulernen. Wir bringen Ihnen die spanischen Originaltexte zusammen mit ihrer Übersetzung in andere Sprachen, einige Notizen und Bilder.

Begleiten Sie uns auf dieser neuen Etappe!

(Crisopeya n.° 8, año ii, febrero 13/22)

* * *

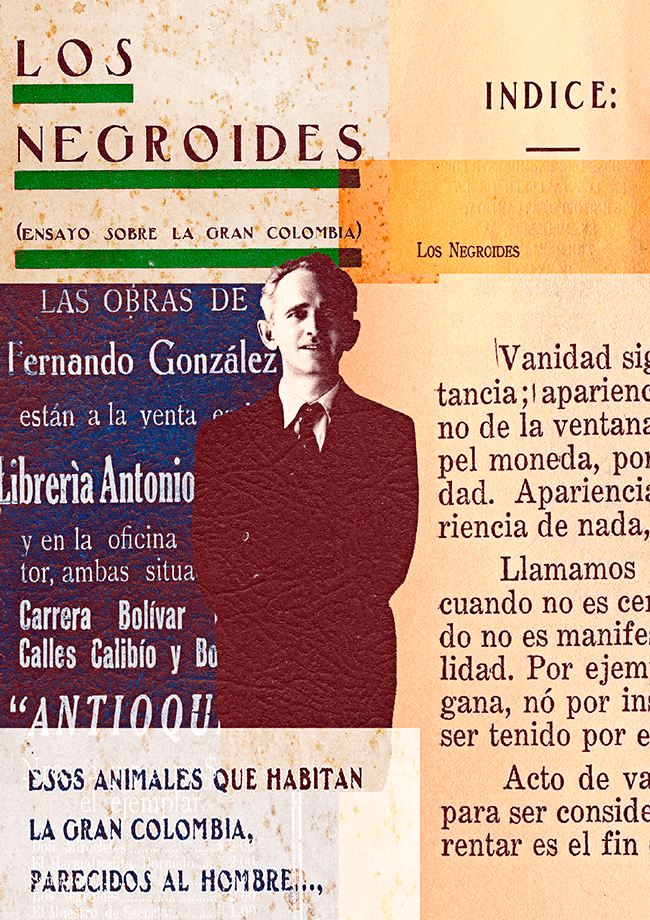

Los negroides

(Ensayo sobre la Gran Colombia)*

Fernando González Ochoa

Esos animales que habitan la

Gran Colombia, parecidos al hombre…

I

Vanidad significa carencia de sustancia; apariencia vacía. Decimos «vano de la ventana», «fruto vano». El papel moneda, por ejemplo, es una vanidad. Apariencia no respaldada, apariencia de nada, eso es vanidad.

Llamamos vanidoso a un acto, cuando no es centrífugo, es decir, cuando no es manifestación de individualidad. Por ejemplo, el estudiar, no por gana, no por instinto íntimo, sino para ser tenido por estudioso.

Acto de vanidad es el ejecutado para ser considerado socialmente. Aparentar es el fin del vanidoso.

Vanidoso es quien obra, no por íntima determinación, sino atendiendo a la consideración social.

Vanidad es la ausencia de motivos íntimos, propios, y la hipertrofia del deseo de ser considerado.

II

La vanidad está en razón inversa de la personalidad. Es social, o sea, no puede existir en el hombre solitario. Es simulación, hurto de cualidades.

Un señor que venera la memoria de su hijo, que vive de la memoria de su hijo, que no habla sino de su hijo muerto, y que si tal hijo no hubiera muerto trágicamente, él lo habría matado, para llorar por él, para vivir del cuento de sus heroísmos y virtudes…: vanidad.

Una señora vieja que se dio a los pobres, a «la gota de leche», a los ancianos, a los tísicos, y que si no hubiera pobres, niños hambrientos, ancianos míseros y tísicos, moriría de tristeza. Tal vieja rica tiene su gloria asentada sobre el dolor ajeno. Dice: «Si Dios quiere, habrá leche para los niños…». Para ella, Dios es el mayordomo de su vanidad; los pobres le forman una corona de beatitud. Tal vieja es jefe del socialismo blandengue de León xiii…: vanidad.

Hay actos y usos que tienen su origen en instintos sociales, como el amor, y que se repiten como formas muertas; por ejemplo, la corbata.

III

La vanidad está en razón inversa de la personalidad. Por eso, a medida que uno medita, que uno se cultiva, disminuye.

La vergüenza es condición de la vanidad; un in-di-vi-duo no tiene vergüenza, no simula. El orgullo es fruto del desarrollo de la personalidad, por ende, contrario a la vanidad. El general Gómez era netamente personalidad, orgullo absoluto y nada vanidoso. Creó modos, usos, costumbres. Las formas manaban directamente de su individualidad; era fuente. En Suramérica hemos tenido dos: Bolívar, hombre etéreo, y Gómez, diabólico, entendiendo por eso que su plano de vida era con las fuerzas elementales, telúricas. Bolívar era cósmico. Maravillas ambos para el observador; maestro, instigador, Bolívar. ¿Entienden ya?

De esto resulta claro lo que he dicho a la juventud, en forma simbólica, en mis libros anteriores: la cultura consiste en desnudarse, en abandonar lo simulado, lo ajeno, lo que nos viene de fuera, y en auto-expresarse. Todo ser humano es un individuo, generalmente cubierto, que generalmente vive de opiniones ajenas. En Suramérica todos están en sueño letárgico; aquí nadie ha manifestado su individualidad, excepto Bolívar, Gómez y algún otro.

Oigan, pues, jóvenes estudiosos, o mejor, juventud que brega en la meditación: el hombre es un espíritu, un complejo, que debe manifestarse, que debe consumir sus instintos en el espacio y el tiempo; apareció el hombre para manifestarse, para actuar según sus motivaciones. La vanidad impide todo eso; el vanidoso muere frustrado, y tendrá que repetir, pues vivió vidas, modos y pasiones ajenos, o mejor, no vivió.

* Crisopeya publica las partes i, ii y iii de este libro aparecido en Medellín en 1936. (Nota de la Revista).

*

The negroids

(Essay about the Gran Colombia)*

Fernando González Ochoa

translated into English

by Rebeca Rendón Cadavid

Those animals that inhabit

Gran Colombia, lookalikes of man…

I

Vanity means a lack of substance; empty appearance. We say «opening of the window», «vain fruit». Paper money, for example, is a vanity. Unbacked appearance, appearance of nothing, that’s vanity.

We call an act vain when it’s not centrifugal, that is to say, when it’s not a manifestation of individuality. For example, studying, not because of want, not for an intimate instinct, but just to be considered a scholar.

A vain act is the one made to be considered socially. To pretend is the goal of the vain.

Vain is who acts not for an intimate determination, but attending social consideration.

II

Vanity is in inverse proportion to personality. It’s social, that is to say, it cannot exist in the lone man. It’s simulation, a theft of qualities.

A man that venerates the memory of his son, that lives in the memory of his son, that doesn’t speak but of his dead son, and that if that son hadn’t died tragically, he himself would have killed him, to mourn him, to live by the story of his heroism and virtues…: vanity.

An old woman that dedicated herself to the poor, to «the drop of milk», to the elderly, to the hectics, and if there weren’t poor people, hungry children, wretched elders and consumptives, she would die of sadness. That rich old lady has her glory held upon the misery of others. She says: «God willing, there will be milk for the children…». To her, God is the butler of her vanity; and the poor form a crown of beatitude for her. That old woman is the boss of the wimpy socialism of Leo xiii…: vanity.

There are acts and uses that have their origin in social instincts, such as love, and that are repeated as dead forms; for example, the tie.

III

Vanity is in inverse proportion to personality. Therefore, as we meditate, as we cultivate ourselves, it diminishes.

Shame is a condition of vanity; an in-di-vid-u-al doesn’t have shame, they don’t simulate. Pride is fruit from the development of the personality, and as such, contrary to vanity. General Gómez was only personality, absolute pride and not vain. He created modes, uses, customs. The forms originated directly from his individuality; he was the source. In South America we have had two: Bolívar, ethereal man, and Gómez, diabolical, understanding by that that his plane of life was with the elemental, telluric forces. Bolívar was cosmic. Marvels both of them for the observer; master, instigator, Bolívar. Do you understand yet?

From this is clear what I have said in my youth, in symbolic form, in my previous books: culture consists of undressing, of abandoning the simulated, the otherness, what comes to us from outside, and in auto-expression. Every human being is an individual, generally covered, that generally lives from other’s opinions. In South America everyone is in a lethargic dream; nobody here has manifested their individuality, except Bolívar, Gómez, and some other.

Listen well, young scholars, or better yet, youth who struggle in meditation: man is a spirit, a complex, that must manifest, that must consume their instinct in space and time; man appeared to manifest, to act according to their motivations. Vanity prevents all this; the vain dies frustrated, and will have to repeat, for they lived lives, modes and passions from others, or better yet, he didn’t live at all.

* Crisopeya publishes parts i, ii y iii of this book that appeared in Medellín in 1936. (Note from the Magazine). Spanish title: Los negroides (Ensayo sobre la Gran Colombia). (Translator’s Note).

Fuente:

Crisopeya n.° 10, año ii, abril 13/22.

* * *

La otra parte

Nicolás Navarrete

(@uy_que_paila)

Collage digital

23 x 17 cm.